June 1, 1963, marked the first day in our beloved Jamhuri of Kenya to have a Madaraka Day Celebration. Only grandparents like me were already born then.

I was three years old when Kenya became independent so I had no clue what was happening then. But our nation was being born in front of all Kenyans from so many different communities falling in love with their country. It wasn’t easy I must guess.

All I know is that 19 years later as a 22-year-old student leader at Nairobi University I was in jail at Nairobi Industrial Area Remand Prison (INDA) from 1982 to 1983 fighting for democracy for our country. And later in 1986 as a lecturer at Mombasa Polytechnic, the Moi government put me at Kamiti Prison for 15 months from Nyayo House Torture Chambers for the same reasons. How the heck did we get there? We will talk about that another day.

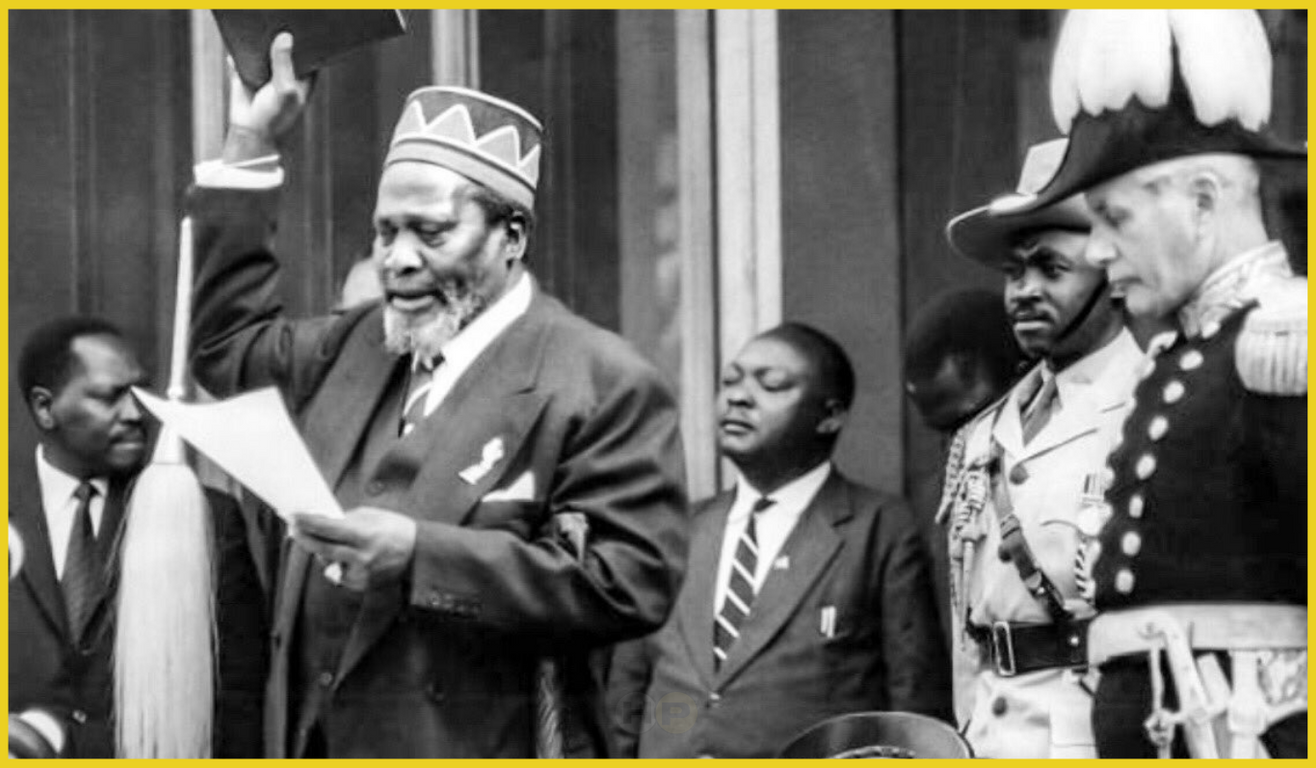

Here is the first Madaraka Day in Kenya.

Then we had a very difficult and beautiful country to build together as all Kenyans working all areas of our lives and that of our country. Let us hear from those who were there then. People like me can keep quiet and just listen to the nation.

Joy was in the air on Kenya’s first Madaraka Day celebrations

On Saturday June 1, 1963, you could have caught happiness in the air if you were at Uhuru Gardens.

It was the day when — after a tumultuous armed freedom struggle — Kenya was becoming the last East African state to be granted internal self-rule by Britain.

Former Assistant Minister Joseph Muturia said he traveled to Uhuru Park in a large Meru delegation organised by area political supremo Jackson Harvester Angaine.

“We had travelled in open lorries, braving the 300km journey between Meru and Nairobi. I think the ceremony had been taken to Uhuru Gardens, far away from the city centre, to keep off large crowds, but the plan failed as people still turned out in large numbers,” said Muturia.

He recalls the enthusiastic reception that key regional leaders such as Tom Mboya, James Gichuru, Paul Ngei, Masinde Muliro, Ronald Ngala, Ngala Mwenda, Daniel arap Moi, Dr. Gikonyo Kiano, Angaine, Jeremiah Nyaga, and Lawrence Sagini received from the crowd.

“It was a befitting start to freedom and economic prosperity for all,” recalls the former school teacher and community development officer who would later be elected for three terms as the MP for Nyambene, Igembe and Ntonyiri constituencies.

“The crowd was electric when Kenyatta took the podium and for the first time in a national event uttered the word Harambee which would become our national motto of pulling together,” said Muturia.

General Ngarari Wanjama, 90, the former chief secretary of Mau Mau Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, was also at Uhuru Gardens to witness the historic event. Having been captured and left the Mau Mau, Wanjama was living in Nairobi with Donald Barnett his co-author of the “Mau Mau from Within” (published in 1966).

“When Kenyatta spoke, the crowd moved with his words. You could see happiness in every face around you. It is like the crowd had also contaminated the air around,” said Wanjama, who yesterday visited the ailing widow of Kimathi at her farm in Kinangop, Nyandarua County.

Field Marshal Muthoni Kirima, one of the last Mau Mau fighters to leave the forest, however, said the day escaped their notice as they were still in the Aberdare forest.

Has Madaraka Day Lost Its Purpose?

By Citizen Reporter Published on: June 01, 2019 01:18 (EAT)

As Kenya celebrates the 56th Madaraka Day on Saturday in Narok County, it brings to the attention of many how the self-seeking journey of liberty in lives of Kenyans has changed since the country attained internal self-rule from the British.

Madaraka is a day of reflection on how Kenya emancipated itself from colonial rule that had inflicted sufferings and suppression for over 68 years.

It reminds of how on June 1, 1963, our founding fathers attained self-rule and Jomo Kenyatta became the prime minister which deemed a new age with positive expectations marked with celebrations.

Today, more than half a century later, countrymen have developed a different perception about the national holiday.

It triggers critics as many are in question whether or not the nation is liberal. This is in line with the fact that it still lags behind in terms of governance and autonomy.

It leads to the main query as to if the country termed as a regional powerhouse has undergone a shift in euphoria or one of melancholy.

With most Kenyans not satisfied with the current state of the nation, the day in itself seems to have lost its purpose.

Prof. Adrian Mukhebi of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University says: “Poverty, diseases and ignorance armed as the key evils the founding fathers were fighting against, are still the key evils affecting Kenya today.”

It raises concern how after such a long time, folks still question the internal self-rule.

A recent random interview by Citizen TV on what and when Madaraka Day is about rendered many citizens clueless. Many showed displeasure due to the current state of the country.

“People aren’t concerned, it seems like a luxury thing and an off-day from work,” one interviewee said. ”I realized that it is a holiday when I watched the news,” he added.

Kenya today still witnesses the effect of full regimes and the solidification of multi-party democracy that formed tribal inclined parties which do not reflect on the unity of Kenyans.

Referred to as the elite’s agenda, it has crumbled the societal values and expectations of Kenyans on patriotism.

A recent act of unity displayed in the March 9, 2018 ‘handshake’ between conflicting leaders: President Uhuru Kenyatta and the former opposition leader, Raila Odinga was the dawn of hope for many freemen.

People expected the wrongs committed earlier would be rewritten. On the contrary, a political shift threatens the very fabric of Madaraka.

Kenya should strive to build a cohesive country by shunning social evils such as corruption in the management of public resources which has led to unemployment and high cost of living.

This menace still poisons the core roots and values in which we stand.

And yes Kenyans are celebrating Madaraka Day in June 1, 2023. The first question for Kenyans is do we still as country have the same problems with the British Colonial rule of Kenya as we had 60 years ago? If we still do we have wasted 60 years in the life of such a wonderful country as Kenya.

Here is what I am talking about.

UK to compensate Kenya’s Mau Mau torture victims

William Hague says payments totalling £19.9m represent ‘full and final settlement’ of action brought by five victims of torture.

Britain is to pay out £19.9m in costs and compensation to more than 5,000 elderly Kenyans who suffered torture and abuse during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s, the foreign secretary, William Hague, has said.

Hague told the House of Commons that the payment was being made in “full and final settlement” of a high court action brought by five of the victims who suffered under the British colonial administration.

“We understand the pain and the grief felt by those who were involved in the events of emergency in Kenya. The British government recognises that Kenyans were subjected to torture and other forms of ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration,” he said.

“The British government sincerely regrets that these abuses took place and that they marred Kenya’s progress to independence. Torture and ill-treatment are abhorrent violations of human dignity which we unreservedly condemn.”

Hague said Britain would also support the construction of a memorial in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, to the victims of torture and abuse during the colonial era.

Hague told MPs that 5,228 Kenyans would receive compensation under the terms of the settlement agreed with their solicitors, Leigh Day.

He stressed that the government continued to deny liability for the actions of the colonial administration and indicated it would defend claims brought from other former British colonies.

“We do not believe that this settlement establishes a precedent in relation to any other former British colonial administration,” he said.

The announcement was warmly welcomed by Martyn Day, senior partner at Leigh Day.

“I take my hat off to Mr Hague for having the courage to make today’s statement and to announce this settlement with our clients,” he said.

“These crimes were committed by British colonial officials and have gone unrecognised and unpunished for decades. They included castration, rape and repeated violence of the worst kind. Although they occurred many years ago, the physical and mental scars remain.

“The elderly victims of torture now at last have the recognition and justice they have sought for many years. For them, the significance of this moment cannot be over-emphasised.”

The settlement comes after a lengthy legal battle between a number of elderly victims and the British government.

The Mau Mau movement emerged in central Kenya during the 1950s to take back seized land and push for an end to colonial rule.

Supporters were detained in camps and thousands were tortured, maimed or executed.

Last year the high court ruled that three Kenyans tortured during the unrest could pursue their compensation claims against the government.

The Foreign Office had attempted to thwart the bid, claiming the actions were brought outside the legal time limit and there were “irredeemable difficulties” in relation to the availability of witnesses and documents.

It did not dispute they suffered “torture and other ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration”.

Lawyers for Wambugu Wa Nyingi, Paulo Muoka Nzili and Jane Muthoni Mara argued that it was an exceptional case in which the judge should exercise his discretion in their favour.

So much for Madaraka for these Mau Mau fighters who sued the British government and the payment is till screwed up by Kenya government even though it is just peanuts.

It would be hard to review our 60 years of Madaraka without looking at the huge land theft called 999 years land lease for free for British colonial companies in this case Finlays and the biggest tea production in the world for the last century on stolen land from Kenyans.

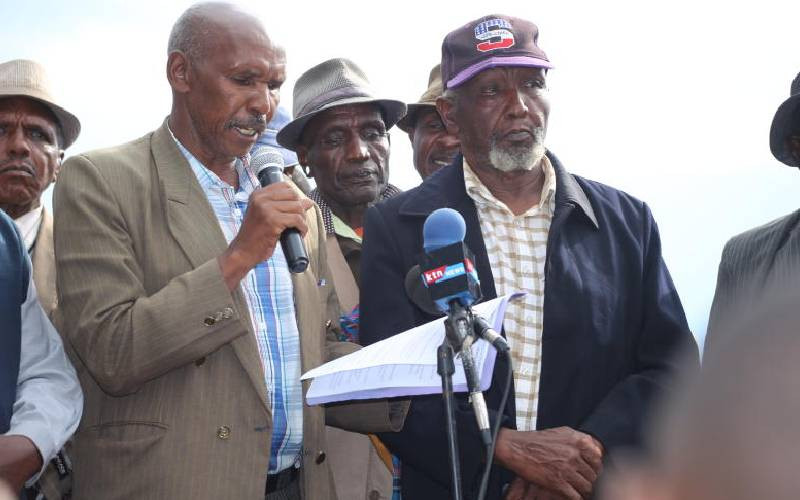

Kipsigis, Talai clans fight for land compensation 60 years on

The Talai and Kipsigis communities have for the last 60 years been fighting for compensation for being evicted from land occupied by multinational companies.

The communities have over the years explored various avenues, including petitioning the National Land Commission (NLC), and Senate and even filing cases in the United Kingdom (UK) to seek compensation for alleged colonial displacement.

They had their woes partly addressed in 2019 in a gazette notice by NLC following a petition by Kericho and Bomet counties on their behalf.

The Kipsigis and Talai, who are the indigenous people in Kericho County, claim they were subjected to gross violations of human rights, including unlawful killings, sexual violence, torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention and displacement, and violations of the rights to privacy, family life and property.

They claim they were evicted from their agricultural-rich land and forced into exile in the tsetse fly-infested Gwasi area in present-day Nyanza, through the 1901 Talai Removal Ordinance. In 1934, the Laibon Removal Ordinance mandated the detention, deportation and internal exile of the entire Talai clan from Kericho County to Gwasi.

Over 500,000 persons belonging to the Kipsigis and Talai are estimated to have been affected by the decree.

For the Talai and Kipsigis, their hopes to have back the land seem to be hitting a dead end.

NLC, in March 1, 2019 gazette notice, said the Kipsigis and Talai were victims of historic land injustices and issued several recommendations.

It recommended that the British government apologises to the Kipsigis and Talai victims, and the State acknowledges that the land should have been returned to the two communities at independence.

It recommended that the British government and the multinationals construct schools, hospitals, roads, a museum, and a university and provide services such as water or electricity to alleviate or compensate for the victims’ suffering.

The British government, NLC said, should also provide direct reparations to victims, adding that the multinational companies lease land at commercial rates. The land with expired leases, NLC said, should not be renewed without the concurrence of the respective county governments.

NLC said the State should identify and acquire land for the purpose of resettling members of the Kipsigis and Talai communities.

Four years later, NLC in what appeared a confirmation of the 2019 Legal Notice in another gazette notice, ordered that all 999-year-old land leases to multinational tea companies in Kericho, Bomet, and Nandi counties be converted to 99 years.

It stated that the renewal of the land leases be withheld until the counties and the multinationals reach an agreement.

On rates, NLC recommended that the same be enhanced to benefit national and county governments.

NLC also recommended that a scholarship fund to educate Talai children be set up by multinational companies holding land in Nandi.

Multinational tea firms had, however, filed a suit at the Environment and Lands Court in Nairobi.

Kenya Tea Growers Association (KTGA) argued that NLC made its determination on the complaint without notifying them of the claims.

KTGA Chief Executive Apollo Kiarie said they were not invited to participate in any sessions between the county governments of Kericho and Bomet. The court noted that no notice was issued to the tea firms.

Justice Oscar Amugo Angote said the application met the threshold for granting the judicial review orders of certiorari and prohibition.

He quashed various recommendations by NLC issued in 2019 in a judgment delivered on April 20, 2023.

The court prohibited the State and Kericho and Bomet counties from implementing the recommendations.

The Senate claimed, in a petition by Kipsigis, Talai, and Borowo communities, that their land was taken away.

The petition claims that Unilever Tea Kenya, James Finlay Kenya, George Williamson, Sotik Tea, Sotik Highlands, Kaisugu Tea, Mau Tea, Koru, and Fort Tenan farms were grabbed from the Kipsigis.

Kipsigis association through Secretary General Joel Kimetto demanded a 100 percent share of James Finlay instead of the 15 percent on Monday.

Their demands follow the sale of the farm to Browns Investors.

That is the State of Madaraka and Jamhuri, ladies, and gentlemen.

I thought it was better to let other Kenyans tell us what is going on.

Loud and Clear. That is all I can say.

How about the Ruto Jamhuri address ? That is for history to judge starting tomorrow. I know I am not history. Thou shall await.

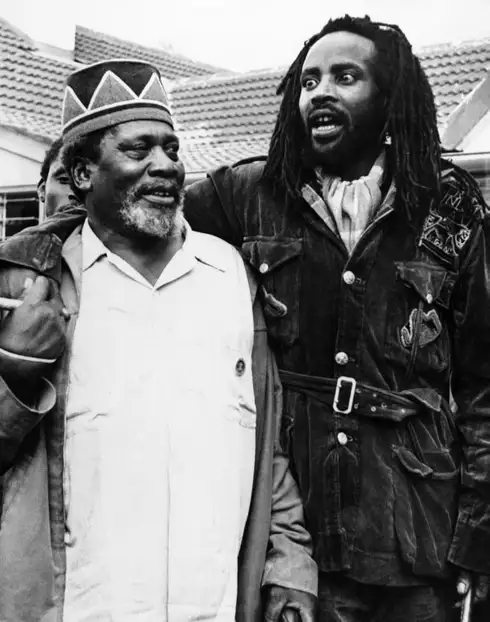

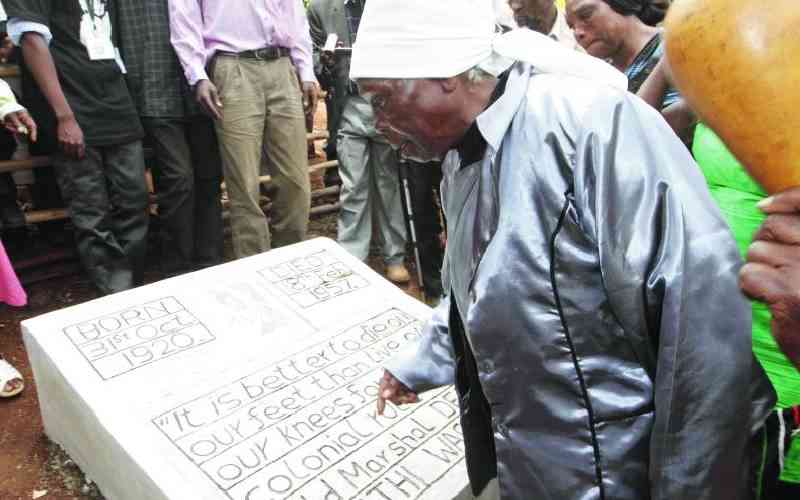

Maybe Dedan Kimathi could have the last word on our Madaraka. This is his story from a writer in Kenya.

Dedan Kimathi: Betrayed by his people in the struggle and after freedom

By Rosa Agutu June 1, 2023

During the struggle for independence in the 1950s, the British colonial administration divided native Kenyans in their attempt to ward off rebellion. One group comprised loyalists who would do anything for their colonial masters.

The other was the hardcore fighters determined to confront the mighty power of the colonial administrators. They did not only stand up against the British; they fought with the loyalists too.

Dedan Kimathi, the poster child for the struggle for independence, was one of fighters who fell victim to the loyalists.

On October 21, 1956, Ndirangu Mau, nicknamed Githimii, shot Kimathi.

Ndirangu was part of home guards sent out to track Mau Mau fighters. He had been employed as a home guard in the 40s with a salary of Sh60 a month.

Ndirangu did not know how Kimathi looked like, but he knew the colonialists would generously reward his captors.

A former editor at the Standard Group, Machua Koinange, recalls his encounter with Ndirangu in 1985. In an article he wrote as a budding reporter, Koinange described Ndirangu, then 79, as a frail man trapped behind a mask of pain.

For close to 29 years, he had remained silent, living under a cloud of resentment and shame that had also been transferred to his children.

The only thing he had to show for the betrayal was a heap of rusted scrap metal of what used to be a truck now stuck in his compound – that truck was never used.

Speaking early this year, Koinange said Ndirangu was reluctant to do the interview, but when he accepted, it was his chance for closure. It was a moment of catharsis for the elderly man.

Ndirangu revealed that at around 6.30am on that fateful day, they caught a glimpse of a man attempting to cross a ditch carrying a bundle.

“We shouted at him to stop but he started running. I fired and missed. I ran after him alone and fired again but missed as he disappeared into the woods.”

He caught sight of him as he tried to jump over a ditch. He fired.

“I had shot him on his right thigh. He was wearing a leopard skin. His bundle of sugarcane was lying next to him. He was holding a panga in one hand.”

He studied the man, perplexed. Finally, he asked in Gikuyu:

“Who are you?”

“Field Marshall Dedan Kimathi Waciuri.”

Ndirangu was stunned.

Kimathi asked him: “Are you the one who shot me?”

“Yes.”

“Ni wega (It’s okay),” Kimathi replied, resigned to his fate.

In the book Mau Mau Freedom Fighter by Mukami Kimathi, her sister narrates the cloud of sadness that engulfed the family when Kimathi was captured. A police officer named Mathuka openly shouted at Ndirangu for shooting Kimathi. He ordered the crowd that had gathered to make a wooden stretcher for Kimathi.

“He then put Kimathi on the makeshift stretcher and hoisted him with others on his shoulder. The hundreds of people who had gathered pushed him out of the way, competing to be the ones carrying the wounded Kimathi. People were fighting to carry Kimathi, exchanging him from shoulder to shoulder every so often so that everyone could have a chance.”

Curse of rewards

Ndirangu was awarded £150 (about Sh25,800 today). Another officer, Njugi Ngatia, who helped him in his operation was rewarded £75 (about Sh12,900 today). The remainder of the £500 reward was divided among the rest of the team.

Ndirangu invest his money in a public transport minibus. Apart from the family, nobody ever boarded the bus.

At night, angry residents would deface the body of the vehicle using stones, writing the words muthirimo wa Kimathi (Kimathi’s shin – the front of his leg that was shot). He would repaint the vehicle, but residents would revisit.

He tried selling it, but nobody was willing to buy “Kimathi’s shin”. The vehicle ended up rusting in his compound.

Ndirangu then opened a restaurant and it met the same fate. Residents would deface the walls with the same words.

Ndirangu lived a life of regret and shame. He was treated as an outcast, and the treatment befell his children. They had a hard time coping in school.

In 1986, Ndirangu died a depressed man.

The others in his team combined their rewards and bought a lorry. The lorry, too, met the same fate as Ndirangu’s bus.

Mukami recalls that the day Kimathi was arrested, she was in Kamiti Maximum Prison. She heard Sirens followed by an announcement.

“Tangazo! Tangazo! Dedan Kimathi, the terrorist leader of the Mau Mau in Kenya has been shot.”

The colonial government even declared a holiday.

“Nobody in the colonial government worked that day. Even in prison, no prisoner was taken out to work. But it was a day of great sadness for mwananchi.”

Kimathi’s capture was a huge relief to the colonialists since law enforcement officers returned their guns to the stores and the British reinforcement battalions that had been brought in were flown out. Prisoners were asked where they came from and would be transported to markets or stadiums near their homes. The colonialists believed the war was over.

Trial and execution

Prof Julius Gathogo, a specialist in oral and ecclesiastical history, says Kimathi’s trial was not fair.

“His was a political case, his trial was supposed to be a political trial like that of Nelson Mandela, where by you do not hang a political prisoner, but they criminalised the case,” he says.

The first judgment was done in haste and when he appealed, the case was quickly dismissed.

An execution report that is kept at the Supreme Court Museum of Kenya indicates that Kimathi was hanged at 6am on February 18, 1957.

The report, signed by a medical officer, indicated that he examined the body and found life to be extinct. Death was caused by hanging and it was instantaneous.

A copy of the judgement that is also kept at the museum indicates that Kimathi was in possession of firearms a.38 Webley Scot revolver, contrary to regulation 8A (1) of the Emergency Regulations, 1953.

This contrasts Ndirangu’s account.

In her book, Kimathi’s widow recalls how prison warders would update her on the progress of the trial. And they would tell her that he will be convicted because everyone in the court apart from Kimathi himself was a colonialist or a sympathiser.

A day before he was executed, Mukami was taken to see him. Upon seeing her, his face lit up and he jumped and hugged her, she wrote.

“Kimathi had a finger on his left hand that had been partly cut while he was grinding grass for cattle. This happened while we were living in Ol Kalou. Many white people had checked his finger as proof that they had captured the right man,” Mukami says in her book.

The British colonialists had promised Kimathi acres of land if he disowned the Mau Mau. He defied. After all, that is what hey were fighting for; ithaka na wiyathi (land and freedom).

“He had two regrets,” Mukami wrote, “that he would not live long enough to see his children grow and that he would not live to see a black man raise a Kenyan flag.”

Kimathi requested his wife not to let the name Kimathi Waciuri die, even if she was to remarry.

It is an honour that Mukami kept.

Unfulfilled dream

She was told to bring the children to see their father for the last time. Little did she know that that was part of the psychological torture that the colonialists used. The children were never to see their father; he was executed at dawn the following day.

Before she died last month, Kimathi’s widow expressed one wish; to bury her husband.

For 66 years she had wanted the government to give her husband a heroe’s burial. During an interview early last year, aged about 93, she said her time was running out and she feared that she may go without seeing her lifelong wish come through.

“The first time she asked for the remains of our father was in 1963, just after (Prime Minister Jomo) Kenyatta was sworn in,” says Mukami’s last born daughter Evelyn Wanjugu, the chief executive of the Dedan Kimathi Foundation.

“Unfortunately, she left this world without giving her husband a decent burial.”

Her brother, Simon Maina Kimathi describes their mother “a hardcore Mau Mau” who never gave up. “Her only wish was to bury her husband. She had so much stress that he health deteriorated.”

Kimathi’s children recall their childhood as one that was influenced by parents who were traumatised by the past.

“Our mother kept asking us if they made a mistake going to the forest to fight for the nation. She kept telling us that it is like being on the field playing football but the trophy is given to the ones cheering,” says Wanjugu.

More than 70 years later Mau Mau fighters still live as slaves in their own country.

After suffering for more than 70 years under the cracking whip of the colonialists who overworked, underpaid and over-taxed them, millions of Kenyans hoped that things would brighten after they got their land and freedom back.

Kenyans thought that now that independence had come, they were indeed free. In their thousands, they came out to celebrate the momentous occasion on a day like yesterday, 60 years ago, optimistic that the worst was over.

They were wrong. Some of the leaders who had fought to steer the country to its new destiny were aghast when the uhuru they had preached and dreamed about for decades proved to be just a mirage. The chipping away of their dream started as soon as the new Kanu administration took the reins of power.

President Jomo Kenyatta’s administration was uncomfortable with Kenya Africa Democratic Union, the opposition which had enjoyed close ties with the outgoing colonial administration, and wary of Britain’s machinations of sowing seeds of discord as was evidenced during the failed army mutiny in January 1964.

The massive concentration of power and resources started as soon as the new administration took over.

The majimbo (federal) system of government was dismantled and the regional semi-autonomous units were starved of cash and ultimately died. The Senate, which was supposed to safeguard them, was also dissolved.

Using the flopped army mutiny of January 1964 as an opportunity to silence its critics, the government banned public meetings in the whole country.

Historian Charles Hornsby writes in Kenya: A history Since Independence, “When the ban was lifted in June 1964, Tom Mboya (Justice and Constitutional Affairs minister) warned that meetings must not be used to undermine established authority or for destructive criticism.”

Then, just like now, the government’s policy was that resources would flow according to its priorities and those who had voted for the opposition would have little role in shaping them.

This mirrors the current debate about government supporters being likened to shareholders who have the right to access plum jobs.

Mau Mau, the proscribed movement whose members fought the colonial forces, has received scant recognition by successive governments and the last remnants of this breed are dying off from old age and ill health after a life of squalor.

When President William Ruto led the nation in marking Madaraka Day in Embu yesterday, many dignitaries were unaware of a nondescript lodging, General Kubukubu, named after a long-forgotten hero, Njagi wa Ikutha, which overlooks the stadium.

General Kubukubu was also fondly known as Citroen by his comrades. He was in charge of freedom fighters in Embu although he had sometimes fought in the platoon named Heka Heka in Nyeri.

Although Kenya is notorious for ignoring its liberators, there are unmatched heroic acts like those of General Baimungi Marete, the uncompromising soldier who battled both colonial and Kenyatta’s government with equal vigour, to correct what he perceived was wrong in his country.

Even after his colleagues came out of the forest in 1963, he waged an armed war against the new government protesting the shortchanging of Mau Mau. Tragically, the general and his followers were gunned down by the very government they had fought so hard to put in place.

Baimungi, the man who took over the mantle after the capture of Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, fought for land and his country and was killed by his government. His family has since been living on a quarter-acre of land. His body was never accorded a decent burial.

And this is a truly sad story that nobody in the Ruto regime talked about in Embu on 60th Madaraka Day.

Hundreds of families still stuck in colonial villages, 60 years after independence

Hundreds of families are still stuck in colonial villages as Kenya marks the 60th Madaraka Day celebrations.

These families have lived in deplorable conditions in the villages for decades.

They have been hoping the government would relocate them or survey land and issue them with title deeds.

The problem of colonial villages emerged in the early 1950s when the British colonial government displaced locals living in the highly fertile land where tea, coffee and dairy farming was at its best due to favourable climatic conditions.

Displaced families were settled in villages surrounded by home guards and run by chiefs who had been deployed by the British settlers.

These villages have now become congested as thousands of families have continued to multiply over the years.

During the colonial era, the British established at least 840 colonial villages. Nyeri County had the highest number of these villages, at 220.

Over the years, most of the villages became towns, and as of 2013, when the devolution set in, 116 colonial villages with 6,583 households were still in existence.

In Nyeri County, at least 983 acres are occupied by colonial villages. The process of demarcation has been slow and painful as families grapple with increasing pressure for more space.

Grace Wanjiru is among the thousands who lived in a colonial village. In 1951, she got married. But barely three years into her marriage, her life was turned upside down; her husband, who was working in Nairobi, away from his home in Kiambu, was detained as the colonial government declared a state of emergency in Kenya. This was during the Mau Mau War for independence.

Wanjiru found herself and her son at the mercy of ruthless home guards alongside hundreds of women in her village.

“Now the women were left to fend for themselves as their husbands worked on farms owned by the wealthy. That is how we were left behind. We could not tell if our husbands would come back or not. And as a matter of fact, some men never returned,” Wanjiru said.

She was one of the lucky few women whose husbands returned. But before they reunited, Wanjiru experienced unimaginable hardship in raising their son by herself.

Life became a struggle for Wanjiru and the other women as they were forced into hard labour for days with no pay and had little or no food to eat.

“The home guards would come to pick us up from the villages in the morning so we can work in the farms. They would blow a whistle in the morning for us to wake up and go to the farms,” she said.

The women would dig the trenches until 1 pm but go home without pay.

“So in the remaining hours, if you had the option of cultivating some sweet potatoes, you would do that so you could, in the process, have something to feed your family with. The forced labour was also accompanied by severe beatings,” Wanjiru said.

Six decades after independence, thousands of families are still living in dehumanising colonial villages. They have been demanding that the villages be surveyed so they can be issued with title deeds or be resettled in alternative land but their efforts have not been successful.

Those living in the villages have little to smile about as they do not own the small pieces of land they live in.

At Kirichu Colonial Village in Nyeri County, Muhia Githenji explained that he inherited his home from his parents, and they had lived all their lives in the small space as a family.

“The trouble with living in a colonial village is we cannot build a permanent house because we have no ownership documents. To make matters worse, we have no access to amenities such as water and electricity,” he noted.

He noted that efforts to survey the village had been slow as there have been disputes over footpaths and communal areas.

“Due to the limited space, we often use footpaths on each other’s property. When the government started surveys, nobody wanted to give up their land to make way for roads or footpaths,” he said.

Nyeri County Lands CEC Ndirangu Gachunia explained that they have made progress in addressing the colonial villages’ issue. Out of the over 200 colonial villages, he said, only 51 have been surveyed.

According to the Nyeri County Budget estimates for the 2023/2024 financial year, the government is intending to spend Sh3 million to plan and survey colonial villages in Aguthi Gaaki, ward, Tetu constituency.

Close to half a century later, generations of the displaced continue to live on the small pieces of land, whose ownership they cannot prove even as the villages continue to remain a sour remnant of colonization.