It took them a few hundred years, 232 to be exact, but finally, the US has a black woman in the Supreme Court and even then it barely happened because the right-wing republicans could not stand even the

thought that this black woman, who is also known to be progressive was going to be in the Supreme Court for the rest of her life.

Yes, we have Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in the house and Michelle Obama put it best when she said Ketanji gives Black women and girls ‘a new dream to dream’. Keep dreaming girls and keep opening those doors that have been locked for so long.

This is one reason why I was getting mad when some lawyers with human rights credentials were telling us last year that the 2010 Kenya constitution is curved in stone and cannot be amended.

I was OK with the likes of Nelson Havi making those claims because I expect nothing else from people like that. But I expected a little more from the likes of Dr. John Khaminwa.

Here is the issue. At some point in the US, black folks were not considered human beings. They were just cattle to farm the lands and feed white people who often just beat them and killed them as a form of entertainment.

White people particularly in the South would come from the church singing loudly to their gods, hold a big BBQ, and have some KKK members bring some blackfellas to be hanged and set on fire to entertain them.

Later on after so many fights and struggles the United States finally accepted that blacks were actually human beings and they had to change their constitution to reflect it. Even that is still an ongoing battle.

Can anybody imagine if the US had declared that their racist constitution was permanent and could not be amended? That is why every constitution has to be amendable because human beings change their

views and values with time. What is good for us today may be terrible a few years from now.

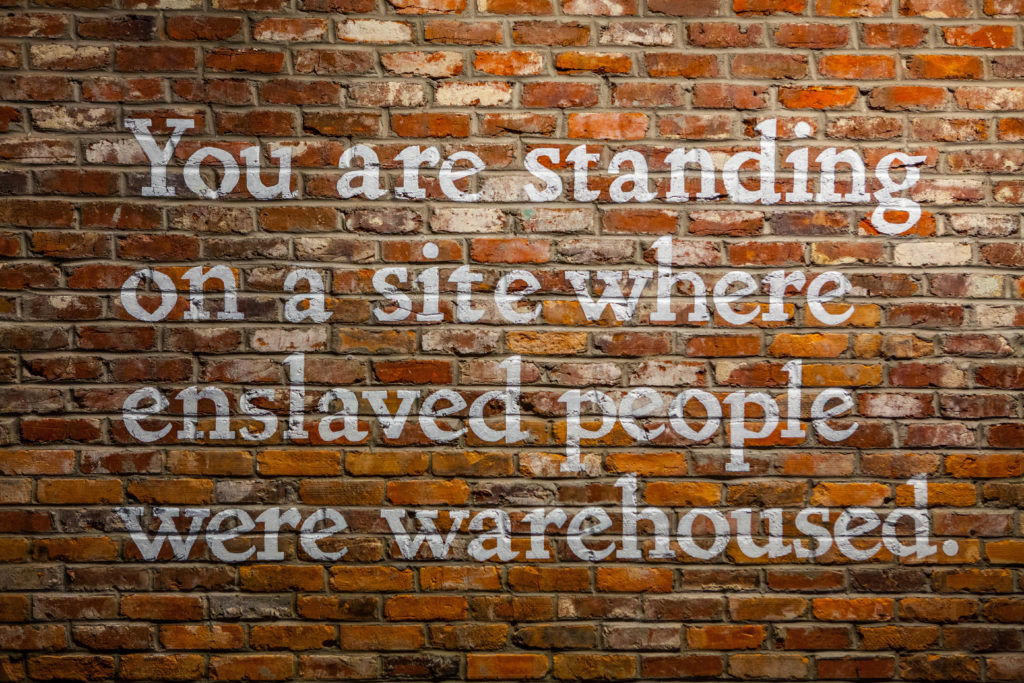

Here is Nia-Malika Henderson’s story on racism in America when she visited the museum in Alabama:

One of my first thoughts, when I arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, and encountered the spring heat, was this:

How did enslaved men, women, and children endure day after day?

It was an odd thought, given that I’m a Southerner, and heat, certainly not spring heat, wouldn’t ordinarily be overwhelming, nor would it lead to thoughts of enslavement.

But here, history is heavy, it’s immediate, and it’s everywhere. And the history that is most on display — in

obvious and not-so-obvious ways — is deeply tied to slavery and its enduring aftermath.

The streets here are named for Confederate generals. The state flag — the St. Andrew’s crimson cross on a field of white — evokes a Confederate flag. There’s a star at the Alabama State Capitol on the spot

where Jefferson Davis became President of the Confederate States.

Not a block away, a young Martin Luther King, Jr. and other activists planned the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott from his basement office at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

On the same street, slave traders once sold women, men, and children alongside cows at bustling slave depots.

There is also the Rosa Parks Museum, the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center, and many murals commemorating the triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement.

All of this, set off from the Alabama River, where slavers once unloaded people to sell, and music lovers and baseball fans now can take in a concert or a game.

The Equal Justice Initiative opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice on April 26 near its headquarters in Montgomery, Alabama. Visitors see Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s sculpture when they walk into the memorial.

It is Alabama’s version of progress, featuring a revitalized downtown that has helped put this city on The New York Times list of top destinations to visit in 2018.

I get into a cab and ask the older, black woman driving me how she likes this new Montgomery.

For her, the new Montgomery can’t eclipse the old. She has a story at the ready, recounting how her father, a veteran, tried to buy a house on a certain block.

The memorial captures the brutality and the scale of lynchings throughout the South, where more than 4,000 black men, women, and children, died at the hands of white mobs between 1877 and 1950.

Most were in response to perceived infractions — walking behind a white woman, attempting to quit a job, reporting a crime, or organizing sharecroppers.

Bryan Stevenson, a Harvard University-trained lawyer who created the Equal Justice Initiative in 1994 to fight for justice for people on death row, found himself transfixed by the South’s history of lynching African Americans.

Stevenson and a team of researchers spent years documenting those lynchings, combing through court records and local newspapers — which often notified the public that a lynching was coming — and talking to local historians and family members of victims.

Naming the victims

Their findings yielded a roll call of names that have never had a place in

the public memory or the public accounting of what happened:

General Lee, lynched in 1904, for knocking on a white woman’s door in

Reevesville, South Carolina.

Jeff Brown, lynched in 1916, for accidentally bumping into a white girl

as he was trying to catch a train in Cedarbluff, Mississippi.

Sam Cates, lynched in 1917, for “annoying white girls” in England,

Arkansas.

Jesse Thornton, lynched in 1940, for failing to address a police officer as

“mister,” in Luverne, Alabama.

“If I asked the question, “Name one African American lynched between

1877 and 1950,” Stevenson said, most people can’t name one person.

“Thousands of black people were lynched. Can’t name one. Why?”

“Because we haven’t talked about it,” he said. “And there are names that

we can call from history for all of these other things. But not that.”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a solemn site, where the naming, claiming — and, Stevenson hopes — healing can begin. His ultimate goal is truth first, and then reconciliation, the kind of processes undertaken after the Holocaust in Germany, the genocide in Rwanda, and apartheid in South Africa.

“I hope it will be sobering but ultimately, inspiring,” Stevenson said. “I hope people will feel like they’ve been deceived a little by the history they’ve been taught and that they need to recover from that. Truth and reconciliation work is always hard. It’s challenging, but if we have the courage, to tell the truth, and to hear the truth, things happen.”

At the memorial, set on six acres of land, the truth is tactile and visceral.

My first encounter is with slavery: A sculpture of a mother, chain around her neck, infant in her arms, registering a horror she can’t escape.

All at eye level. Enslaved black bodies, close up.

As the procession moves forward, the weight and the dread intensifies. The floor beneath the monuments begins to slope, and the bodies begin to rise.

This is what black communities in the south saw over and over again. Black bodies, mutilated and raised up, as a clear threat. Lynching “was intended to terrorize communities of color, and that’s

why all black folks in these communities were victims,” Stevenson said.

“Sometimes they would leave the body hanging on a tree, and the family would come to claim it, and they wouldn’t let them. It was the optic of this raised violence that made the threat, the menace even more powerful.”

Surrounding the memorial, replicas of each of the monuments will also be on display. Each county represented here will have the opportunity to take one of the figures back to their communities as a way to remember and to begin a conversation. It will also be obvious which counties do not claim their monuments.

The opportunity is also a challenge — which counties are ready for truth and reconciliation? Stevenson said that EJI has already been contacted by a few counties interested in claiming their monuments.

“I think people are never fully ready. It’s always a challenge, but that’s why it’s so important. That’s why it’s so urgent. You could say that this country wasn’t ready for emancipation in 1865. You could say it wasn’t

ready to give up lynching,” Stevenson said.

“You could say it wasn’t ready for the Montgomery bus boycott. It wasn’t ready for the civil rights movement, but it is necessary because there are too many of us who want to be free, and we can’t get to

freedom if we don’t talk more honestly about our past.”

Seeing the suffering and strength.

This sculpture, by the Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, is a rendering of enslavement that has rarely been seen in any public space.

“We want people to see the pain. We want them to see the suffering. We want them to see the anguish,” Stevenson said. “But we also want them to see the humanity, and the strength, and the dignity and the capacity to endure.”

On a hill overlooking the sculpture, I see the memorial square, where more than 800 steel monuments hang. Each monument represents a county where lynchings took place, listing names of people most of us have never heard of.

People like Irving and Herman Arthur, burned to death on July 6, 1920, before a mob of 3,000 at a fairground in Paris, Texas. Elizabeth Lawrence, a teacher lynched in 1933 in Birmingham because she told a group of white kids not to throw stones at people.

The walk up the hill to the hanging monuments feels like a funeral procession, a dreadful and burdensome journey to a collection of headstones. Standing side-by-side with one of the monuments, I reach out and touch it, taking in the names, grabbing it, bringing it closer.

“Initially, we thought, ‘Oh, it should be pristine and beautiful,’” Stevenson said.

Then they thought, “No. This is painful history,” he said. “This is an ugly history. When it rains, the steel actually drips this kind of rustycolored water and you’ll see it actually stain the perimeter, and it almost looks like they’re bleeding.”

“When the monuments started to come and when they arrived, the thing that completely blew me away that I hadn’t thought about before, was seeing those names. It just made it personal.”

Black bodies rising up

The companion museum extends the narrative from slavery to present-day mass incarceration, and makes what to some might be a bold claim — slavery’s foundational theory, that blacks are inferior to whites, wasn’t abolished. It merely evolved.

Signs from the Jim Crow era will be familiar to most. What might be less familiar is the detailed ways that every aspect of life was ruled by racism.

A 1952 code in Montgomery, Alabama, made it illegal “for a negro and white person” to play cards, dominoes, or checkers.

Interracial billiard playing was also illegal. Also illegal in Atlanta, Georgia in 1942, was “a colored baseball team” playing “within two blocks of a playground devoted to the white race.”

“We shouldn’t think of segregation as just that particularly ignorant relative that says the n-word,” Stevenson said. “We have to understand it as a system that had a legal architecture, and everything was included.”

On the back wall, there is a black and white photo of black men in a cotton field. It appears to be a slavery-era photo, but it isn’t.

It’s from a Texas prison in the late 1960s.

“Some people are provoked by the idea of slavery and mass incarceration in the same space,” Stevenson said. “This picture gives insight on why we’re talking about this.

Southern prisons made incarcerated people pick cotton until the 80s and early 1990s.”

“That’s where that language in the 13th amendment that prohibits slavery except for people convicted of crimes becomes so relevant. This isn’t an accident.”

Formerly incarcerated African Americans — some finally declared innocent and others freed after time served — tell their stories from behind the glass of a prison visiting booth rebuilt at the museum. And

letters from inmates, some juveniles, line the back walls.

But the most powerful aspect of the museum is as I enter.

Immediately, there is a sense of place as the museum is on the ground where enslaved women, men, and children were kept in slave pens. A dark hallway leads to an encounter with an enslaved woman looking for her children.

To hear her story, her pleas for her lost children, I have to lean close, pressed up against the bars that contain her. I feel anxious, uncomfortable, and penned in.

Visitors will no doubt linger here, where the enslaved, old and young, appear almost like ghosts.

“There is power in those who endured slavery. There is a strength in those who found a way to survive in these spaces, despite the threat of violence, despite the threat of terror and violence,” Stevenson said.

Thanks to these people.

“There is a dignity and a grace that comes with having to navigate segregation year in, year out. And I feel like, I’ve got to wrap my arms around that and use it to persuade others that we can do better.”

Adongo Ogony is a Human Rights Activist and a Writer who lives in Toronto, Canada