Brazil is probably one of the most complicated countries in the world. Maybe we know about Pele. Real name Edson Arantes do Nascimento. But we know very little else about Brazil.

Brazil has a population of 220 million people. There are more black people in Brazil than in the United States. How the heck did they get there?

I used to have fights with my buddy from Colombia who loves football and was very happy about Brazil’s football. I was telling him the people who play football in Brazil and who have made them so famous are black and yet the black folk in Brazil are treated like dirt.

Who is Lula?

In 1980 Lula and a group of workers, intellectuals and artists founded the Workers’ Party in response to the military regime, a pluralistic left-wing party that brought together trade unionists, intellectuals, artists, and liberation theology practitioners, among others.

He ran for the presidency three times before being elected in 2002, becoming part of Latin America’s pink tide. During his time, Brazil enjoyed an economic boom triggered by an uptick in the global demand for commodities, and his time in office is remembered for massive social welfare programs that lifted millions out of poverty.

Why was he in prison?

In April 2018 Lula was sent to prison for corruption as part of the “Operation Car Wash” (“Lava Jato”) investigation, heralded by Judge Sérgio Moro. The sprawling investigation looked into a kickbacks scheme involving Brazil’s state oil company Petrobras that had ramifications across Latin America.

Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that inmates cannot be jailed if their appeals are still pending, a decision that affected thousands of prisoners, among them Lula. The court’s decision came days after The Intercept published revelations that Moro had collaborated with prosecutors during the former president’s case, breaking the rules of due process. Lula was released in November of 2019 after spending 580 days in prison.

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has done it again: Twenty years after first winning the Brazilian presidency, the leftist defeated incumbent Jair Bolsonaro on Sunday in an extremely tight election that marks an about-face for the country after four years of far-right politics.

It is a stunning return to power for Lula, 77, whose 2018 imprisonment over a corruption scandal sidelined him from that year’s election, which brought Bolsonaro, a defender of conservative social values, to power.

“Today the only winner is the Brazilian people,” da Silva said in a speech at a hotel in downtown Sao Paulo. “This isn’t a victory of mine or the Workers’ Party, nor the parties that supported me in campaign. It’s the victory of a democratic movement that formed above political parties, personal interests, and ideologies so that democracy came out victorious.”

Lula is promising to govern beyond his leftist Workers Party. He wants to bring in centrists and even some leaning to the right who voted for him for the first time and to restore the country’s more prosperous past. Yet he faces headwinds in a politically polarized society where economic growth is slowing and inflation is soaring.

His victory marks the first time since Brazil’s 1985 return to democracy that the sitting president has failed to win re-election. The highly polarized election in Latin America’s biggest economy extended a wave of recent leftist victories in the region, including Chile, Colombia, and Argentina.

It was the country’s closest election in over three decades. Just over two million votes separated the two candidates with 99.5 percent of the vote counted. The previous closest race, in 2014, was decided by a margin of 3.46 million votes

Lula’s inauguration is scheduled to take place on Jan. 1. He last served as president from 2003 to 2010.

Congratulations for Lula — and Brazil — began to pour in from around the world Sunday evening, including from U.S. President Joe Biden, who highlighted the country’s “free, fair, and credible elections.” The European Union also congratulated da Silva in a statement, commending the electoral authority for its effectiveness and transparency throughout the campaign.

“Four years waiting for this,” said Gabriela Souto, one of the few supporters allowed in due to heavy security.

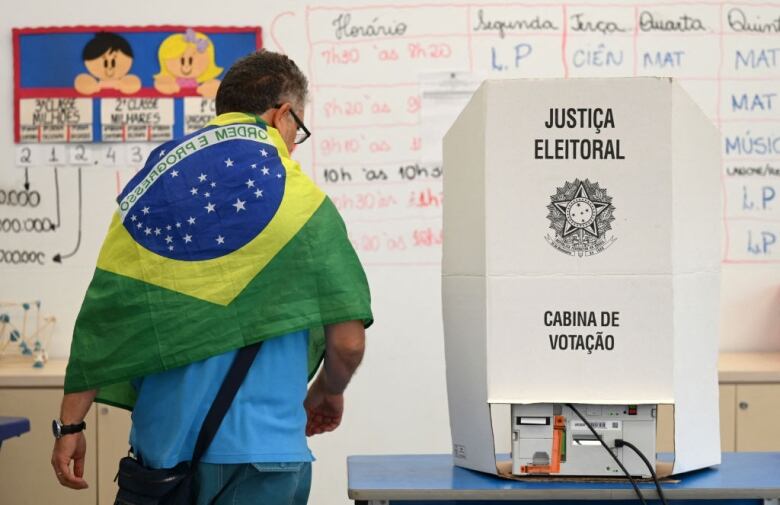

A voter draped in Brazilian national flag is seen at a polling station in Brasilia on Sunday.

Outside Bolsonaro’s home in Rio de Janeiro, ground zero for his support base, a woman atop a truck delivered a prayer over a speaker, then sang excitedly, trying to generate some energy. But supporters decked out in the green and yellow of the flag barely responded. Many perked up when the national anthem played, singing along loudly with hands over their hearts.

Lula has also pledged to put a halt to illegal deforestation in the Amazon, and once again has prominent environmentalist Marina Silva by his side, years after a public falling out when she was his environment minister. The president-elect has already pledged to install a ministry for Brazil’s original peoples, which will be run by an Indigenous person.

In April, he tapped center-right Geraldo Alckmin, a former rival, to be his running mate. It was another key part of an effort to create a broad, pro-democracy front to not just unseat Bolsonaro, but to make it easier to govern. Lula also has drawn support from Sen. Simone Tebet, a moderate who finished in third place in the election’s first round.

“If Lula manages to talk to voters who didn’t vote for him, which Bolsonaro never tried, and seeks negotiated solutions to the economic, social, and political crisis we have, and links with other nations that were lost, then he could reconnect Brazil to a time in which people could disagree and still get some things done,” Melo said.

Adongo Ogony is a Human Rights Activist and a Writer who lives in Toronto, Canada