During the 1800s, roughly 100,000 enslaved Africans in the US sought freedom on the Underground Railroad, a network of people and safe houses that formed a series of escape routes that stretched from the American South to Canada and Mexico.

The large-scale coordination and collaboration under such dangerous circumstances was a remarkable feat. Here are seven facts about the Underground Railroad.

1. The Underground Railroad was neither underground nor a railroad.

Unlike what the name suggests, the Underground Railroad was not subterranean. It was a metaphor for a network of people and safe houses that helped people fleeing slavery attempt to reach freedom.

No official membership was needed to be a part of the network; those who helped included formerly enslaved people, abolitionists, and ordinary citizens. The underground railroad provided food, shelter, clean clothing, and sometimes even help finding jobs for those seeking freedom.

It is unclear when and how the term Underground Railroad came to be used for this network. Some say it arose after an incident in 1831: An enslaved person named Tice Davids swam across the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio, a town known for having a strong Underground Railroad network. His old enslaver, angry that Davids had successfully fled, reportedly said, “He must have gone off on an underground railroad.” Others attribute the term to William Still, a prominent abolitionist.

2. People used train-themed codewords on the Underground Railroad.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 made slave-catching a lucrative business.

Talking in plain-speak was a surefire way for both enslaved people and those helping them to get caught by those looking to cash in on a bounty. To avoid detection, people used a system of widely understood train-themed codewords. It made sense: Train lines had started popping up across the US, providing the perfect cover.

Safe houses were dubbed “stations” or “depots.” Those who invited freedom-seekers into their homes were called “stationmasters,” and those who helped guide them on their path were called “conductors.” Terms like cargo referred to the enslaved people, while stockholders referenced those who helped financially.

3. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it harder for enslaved people to escape.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was part of the Compromise of 1850, was one of the most extreme slave laws to be passed. It made the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793—which gave slaveholders the right to recapture freedom seekers—stronger and called for harsher punishments for freedom-seekers and those who tried to help them.

Some of the Northern States strongly opposed the 1793 Act and enacted the Personal-Liberty Laws, which provided the freedom-seekers the right to a trial by jury if they appealed the original decision against them. Pressure from the South for stronger laws resulted in the 1850 Act. The revised Act increased the penalties for helping slaves to $1000 and six months in jail. It also took away the right for freedom-seekers to have jury trials and testify on their behalf.

4. Harriet Tubman helped many people escape on the Underground Railroad.

Harriet Tubman used the Underground Railroad in the fall of 1849, escaping from the Poplar Neck Plantation in Maryland to Pennsylvania, a free state. She went on to become a famed conductor, helping around 70 people—estimates vary—over 13 trips to the South. On her third trip to help enslaved people, she tried to convince her husband to leave with her; he had already remarried and refused.

Tubman was revered as “Moses” and respected as “General Tubman.” She also took an active part in the Civil War as a cook and a nurse at refugee camps in the South, where she aided enslaved people who had escaped.

Eventually, she worked as a spy to map the region, and even led 150 soldiers in their raid of the Combahee Ferry in June 1863, freeing 700 enslaved people.

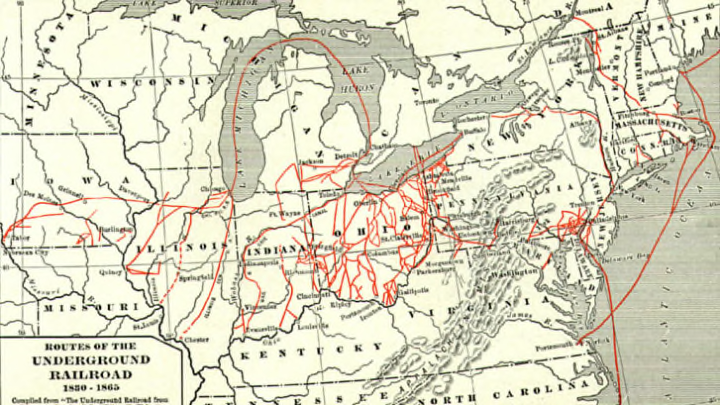

5. Not all Underground Railroad routes went to Canada.

With the Fugitive Slave Act in effect, the Northern States were also not safe for freedom-seekers—there was always the risk of them being found and sent back to the South.

For them, Canada seemed like the best option. Two went routes to Canada: One followed the Mississippi and Ohio rivers into the Northern States and onward to Canada, and the other wound along the Eastern Seaboard. Members of the Underground Railroad even helped formerly enslaved people who reached Canada settle in this new country.

However, for some enslaved people in the deep South, making it to Canada seemed like an unachievable task. Fortunately, two of the four main Underground Railroad routes went south.

Those seeking safety with the Seminole Indians or hoping to reach the Bahamas passed through Florida; another trail skirted the Gulf of Mexico before leading into Mexico. The freedom-seekers would often purposefully go the wrong way for a bit or take a roundabout route to rid the bounty hunters on their heels.

6. William Still was considered the father of the Underground Railroad.

Born October 7, 1821, William Still was a prominent abolitionist and a chief conductor in Pennsylvania. Along with aiding freedom-seekers directly, he kept meticulous records of those he helped, hoping the records would one day reunite families.

Still is said to have helped at least 649 people escape, each of whom he interviewed about their family and the struggles they faced during their escape. His detailed questions helped him realize that one of his interviewees was actually his elder brother, Peter, who had been re-sold after their mother’s escape from slavery (Still had been born after her escape). Peter was reunited with his mother after 42 years.

By keeping these detailed notes, Still was not only putting himself at risk: If the diary had been found, the lives of everyone he documented would be in peril. Fortunately, his notes never fell into the wrong hands, and Still turned them into a book published in 1872.

7. Henry “Box” Brown escaped along the Underground Railroad by mail.

Henry Brown was born on a plantation in Louisa County, Virginia. In 1836, he married Nancy, an enslaved woman with a different slaveholder. The couple had three children; when they were expecting a fourth, Nancy was sold and sent off to a family at a different location. This prompted Brown to escape.

When figuring out the safest and surest ways to escape, inspiration struck. Brown decided to put himself in a wooden box that was 3 feet long, 2 feet wide and 2.5 feet deep. He labeled the container as “dry goods” and shipped himself from Richmond, Virginia, to the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society.

After the almost 250-mile journey—which took 27 hours and almost killed him—Brown reached to safety. He lost consciousness after being let out of the box, but awoke to sing his own version of Psalm 40, later dubbed the “Henry ‘Box’ Brown Song.” After he became a free man in 1849, Brown took up speaking gigs across the States, talking about his journey, and even brought along a moving panorama displaying his escape.

But he never reunited with his children and wife, despite being contacted with offers for their freedom. He went on to marry another woman in England, and had a daughter with her.