According to a statement from the committee, this was in recognition of Were’s tireless work since the 1970s in promoting trust between governments, health authorities, and the citizens through culturally sensitive programs.

Were’s focus has been on community health approaches, the efforts which they argue facilitate the uptake of health initiatives among the vulnerable people, including the ongoing COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

“It is an honor to have the opportunity to nominate Dr. Miriam Were for the Nobel Peace Prize,” said Joyce Ajlouny, General Secretary of AFSC.

She added “Over the last two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical importance of public health policy and global health equity. Dr. Were’s work on community-based health initiatives around the world is powerful and essential for building a just and peaceful future.”

While expressing her gratitude for the nomination, Were pointed out that she believes in “community approach as the modality for promoting both peace and health by empowering individuals and communities to lead in solving their problems including those articulated in the Sustainable Development Goals.”

Were graduated from the University of Nairobi with a medical degree in 1973 followed by master’s and doctorate degrees in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University in 1976 and 1981, respectively.

She had served in the health sector for close to 50 years.

Some of her most notable professional positions include directing the Community-Based Health Care (CBHC) Project in Kakamega, Western Kenya; serving as Chief of Health and Nutrition in UNICEF Ethiopia and working as WHO Representative and Chief of Mission in Ethiopia.

She also directed the UN Population Fund Country Support Team (UNFPA/CST) for East and Central Africa and Anglophone West Africa.

Were is also the founder of the UZIMA Foundation, an NGO for youth empowerment. She currently serves as Chairperson of the National AIDS Control Council (NACC) Kenya coordinating the national HIV/AIDS response in Kenya. She is on the Lancet COVID-19 Commission.

In 1947, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Friends Service Council (the precursor to QPSW) and AFSC on behalf of Quakers worldwide for their work during and after the two world wars to feed starving children and help Europe rebuild itself.

The organizations use their nomination to highlight the work of others continuing the vital work of peacebuilding.

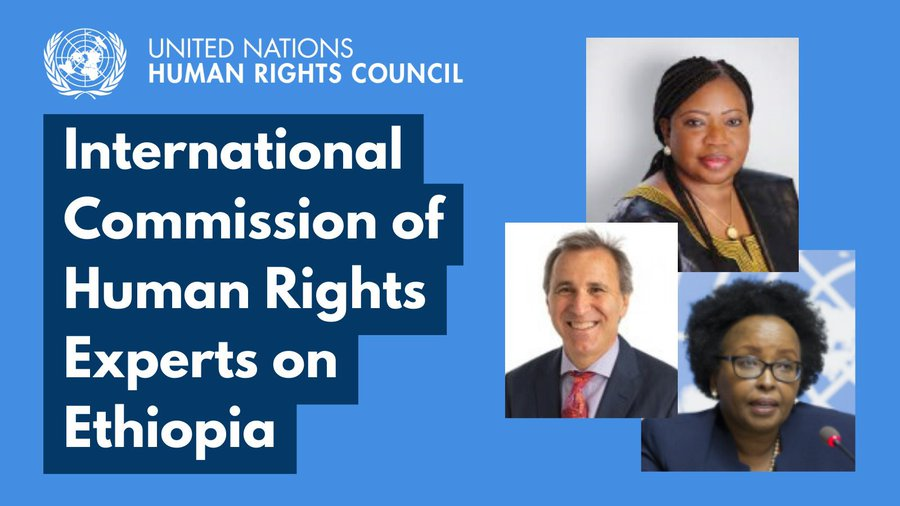

A few days ago a prominent Kenya lawyer who has been in the struggles for human rights in our country for decades, Betty Kaara Murungi, was appointed together with Fatou Bensouda (Gambia) and Steven Ratner (USA) by the United Nations Human Rights Council UNHRC) to investigate alleged human rights violations and abuses in Ethiopia during the war with Tigray.

Through resolution S-33/1 of 17 December 2021, adopted at its special session, the Human Rights Council decided to establish an international commission of human rights, to be appointed by the President of the Human Rights Council, to conduct an impartial investigation into allegations of violations and abuses of international human rights, humanitarian and refugee law in Ethiopia committed since 3 November 2020 by all parties to the conflict.

The three-person Commission was also asked to “establish the facts and circumstances surrounding the alleged violations and abuses, collect and preserve evidence, to identify those responsible, where possible, and to make such information accessible and usable in support of ongoing and future accountability efforts”.

With the same resolution, the 47-member body mandated the Commission to build upon the report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and to make recommendations on technical assistance to the Government of Ethiopia in support of accountability, reconciliation, and healing.

The Commissioners, who will serve in their personal capacities, were also requested to present an oral briefing to the Human Rights Council at its 50th session in June/July 2022 and a written report at its 51st session in September/October this year.

The great news here is that these are Kenyan global leaders doing their work quietly in relative obscurity while working on some of the most important and urgent matters that affect our universe as human beings.

They demand and ask nothing from us. Not even the recognition they deserve so richly. Maybe we are not watching or paying attention but the world is indeed watching and paying attention and that is a good thing.

The irony of it all is that if we could have implemented some of the great ideas and initiatives by someone like Dr. Miriam Were who worked tirelessly to facilitate access to medicine and health care services to the ordinary population.

The Community-Based Health Care (CBHC) model Dr. Were set up in Kakamega years ago is now the range in the healthcare provider communities and those who need health services. CBHC model takes healthcare to the doors of the communities who need it instead of the other way round. This model saves time, resources, and lives.

Yes, Kenyan communities both in urban and rural areas need the big hospitals whether at county levels in various population areas and all that, but countries are better off taking healthcare services close to the communities that need and use them.

That is what Dr. Were has learnt and worked on for 5 decades. Teaching and spearheading practical initiatives to bring healthcare services nearer to the people where they live and work.

Our country could do with Dr. Were’s input on these things and it is good to know that she is currently involved at the highest level in working for good and better healthcare systems for Kenyans.

In Kenya today health care work itself is a hazard especially in public health hospitals and facilities run by the county governments and the national government.

During the pandemic, the national healthcare professionals including doctors working without adequate protection were exposed to diseases and some have died as a result.

That is not a new thing in Kenya. In the last 10 years, the entire public medical service system that millions of Kenyans rely on because they cannot afford to pay for private medical services has been in turmoil that never ends.

Every day in Kenya there is a group of healthcare providers on strike and often it is because the county governments which are supposed to pay them have not done so sometimes for months. In some cases, there are strikes by healthcare providers across the country for failure to pay.

Predictably our politicians never even notice that problem obviously because it doesn’t affect them. Not one single politician ever talks about how to provide for healthcare providers to avoid strikes. The politicians just want you to believe that the healthcare workers going on strike are the evil ones leaving people to die.

How about the county governments misusing healthcare budgets? How about the national government allocating so much money from the ministry of health to themselves when they don’t provide services to the people depending on county hospitals?

The key to solving the gridlock and lack of services in our public healthcare system lies in sorting out the funding system and how the total budget in the ministry of health is allocated between the counties and the national government on the basis of who has which responsibilities to provide Kenyans with good public health services.

If counties are going to pay salaries and benefits to healthcare providers under their jurisdiction then they need the money and if they misuse the money they have to be tossed out of office mara moja.

No more confusion about which branch of government is funded for which service. Get it done.

Kenyans have also taken notice of Betty Kaara Murungi who has been appointed to the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and I think even she recalls the big battles for Women’s Rights in Kenya Kenya which took two faces.

First was the battle for the BOMAS new constitution just after President Mwai Kibaki took office in 2003. It was in that battle that women involved in the fight for a new democratic constitution like Betty Murungi put on the table the demand for equal rights and equal representation of Kenyan women in our institutions of power including the National Assembly.

It wasn’t easy because men politicians always say the same thing oh just run for whatever seat you want and if you win fine but no need for legal requirements for minimum representation.

Of course, they say this in a country where half the population is female. They work, they teach, they provide healthcare, they are farmers, they are doctors, they are politicians, they run businesses and all of it but no they can’t get at least minimum representation. That battle was fought and won on the battlefield by women activists.

Today in the 2010 Kenya constitution there is a constitutional requirement that at least 1/3 of the National Assembly has to be of either gender. Simply put women M.Ps have to be at least 1/3 of the total number of M.Ps otherwise anything enacted in that parliament should be null and void.

But do you think they care? Not the politicians and not the judiciary where the Supreme Court just refuses to give a definitive legal authoritative ruling as to whether our current parliament which has not conformed to constitutional 1/3 requirement is legal. What a sad question to ask. Whether your parliament is legal

In terms of fundamental rights for women in Kenya, we are still way behind.

Sometime back a group of us here in Toronto came up with a document which we published on March 8 which is the International Women’s Day when we went to a public forum.

The piece is entitled: “Women’s Rights Are Human Rights”

In regards to Kenya here are a few of the requirements that women in our group talked about.

1. Equal rights and duties in the family

2. The right to work and get equal pay for equal work

3. The right to education, health and access to land, farm inputs, marketing extension services

4. The right to own, inherit, purchase and dispose of property.

I will just leave it there for now. There are 20 others.

But I was asking myself how many of those have we achieved and how many are we still struggling with.

Finally, we may just examine a bit The Legacy of Wangari Maathai as enumerated by her colleagues in the environmental movement across the globe.

Among the most prominent environmental activists of the last century is the late Professor Wangari Maathai, who founded the Green Belt Movement and inspired hundreds of thousands of people around the world to push for environmental progress. In commemoration of the 30th anniversary of her 1991 Goldman Prize win—and the 10th anniversary of her passing—we’re remembering Wangari’s rich background and innumerable contributions to both the environment and human rights.

Determined from the Beginning

Wangari Maathai with the Ouroboros after winning the 1991 Goldman Prize for Africa

Born in 1940 in Nyeri, Kenya, Wangari spent her childhood in the Kenyan countryside and her young adult life in the United States. She studied biology at Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas, then obtained a master’s degree in biological sciences from the University of Pittsburgh. After returning to Kenya and pursuing her PhD at the University of Nairobi, Wangari became the first woman in East Africa to receive a doctorate.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, along with teaching at the University of Nairobi and serving as a department chair, Wangari was an active member of the National Council of Women of Kenya, an organized group of rural Kenyan women fighting for women’s rights. Women came to the council in part to search for solutions to the environmental degradation they were witnessing in their villages; deforestation and desertification had caused many of the resources women relied on for food and clean water to dwindle.

Fueled by her knowledge of biology and innate passion for helping others, Wangari decided to take action.

Solving a Problem, Starting a Movement

Wangari had two goals in mind: to help restore environmental resources and give women the ability to support their families in a self-sufficient, sustainable way. To achieve her goals, she came up with a practical but impactful idea: to grow seedlings and plant trees. The trees would counteract the effects of deforestation, bind the soil, and improve rainwater sequestration, in addition to providing food and firewood—and, therefore, a livelihood for local families.

Wangari’s plan inspired the formation of the Green Belt Movement in 1977, an organization dedicated to environmental conservation and poverty reduction in Kenya. As the work of the movement evolved, Wangari realized that the environmental issues impoverished communities faced were a direct result of bigger problems, like governmental corruption and a history of disenfranchisement.

To help address the root causes of these concerns, the organization began leading what are now called Community Empowerment and Education seminars, meetings designed to educate community members about the environment and their civic rights.

Expanding Her Influence

As the Green Belt Movement grew and began to inspire tree-planting missions across the continent, Wangari expanded her focus. A champion of both social justice and the environment, Wangari’s activism sat at the intersection of several different but intertwined causes: environmental conservation, democracy, and human rights.

Wangari used grassroots activism to lead important protests throughout the decades that followed. In the late 1980s, she mobilized her community to oppose the construction of a skyscraper in Uhuru Park, Nairobi’s central public space. Though international investors eventually backed out the project as a result of her opposition, the Kenyan government and press vilified both Wangari and the Green Belt Movement in the process.

Efforts to thwart Wangari’s influence and activism only intensified. In 1992, Wangari participated in a hunger strike in Uhuru Park to advocate for the release of political prisoners—and the police beat her unconscious. Then, in 1999 she led a protest against the privatization of Karura Forest in Nairobi, during which Green Belt Movement members were beaten by private guards. Despite facing ongoing repression and opposition from powerful actors in the region, Wangari never wavered in her work.

Creating a Legacy

Wangari served on the boards of countless environmental organizations, spoke to members of the United Nations, and represented her community as a member of Kenya’s parliament for several years in the early 2000s. Due to her tireless work as both an environmental activist and humanitarian, Wangari received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.

After winning the prize, she was appointed Goodwill Ambassador for the Congo Basin Forest Ecosystem, wrote four books (The Green Belt Movement, Unbowed, The Challenge for Africa, and Replenishing the Earth), and continued speaking and advocating for greater representation within the global environmental movement.

Today, Wangari lives on through the countless lives she’s touched, and through the Green Belt Movement, which has continued its work in Kenya and globally through international tree-planting and climate change advocacy. Her daughter, Wanjira Mathai, continues her legacy as a prominent environmental advocate and member of the Goldman Prize Jury.

Every one of us—regardless of geography or background—can honor Wangari’s lifelong work and support her legacy by taking a few simple steps.

In her famous “Rise up and walk” speech, Wangari said that we can start by planting 10 trees to offset the carbon dioxide we each exhale; practice the philosophy of reducing, reusing, and repairing; and look for opportunities to volunteer our time and services to our communities.

Adongo Ogony is a Human Rights Activist and a Writer who lives in Toronto, Canada