When the Ndegwa Commission Report was finally tabled in Parliament in 1974, three years after it had been written, it marked a turning point in Kenya’s political and economic history.

Burudi Nabwera, then a Member of Parliament for Lugari, famously described it as “a cancer that will destroy this country.” His words would prove prophetic. The report, which legitimized civil servants engaging in private business, effectively sanctioned corruption at the highest levels of government.

What had previously been an undercurrent of opportunism now became official policy. The state had, in essence, legalized self-enrichment.

The Ndegwa Commission and the Institutionalization of Corruption

The 1971 Ndegwa Commission was ostensibly established to examine the structure and remuneration of the public service. However, its most consequential recommendation was that civil servants be allowed to own businesses and participate in private enterprise. This blurred the line between public duty and private interest. Ministers, permanent secretaries, and senior bureaucrats began using their offices to accumulate wealth, often through kickbacks, inflated contracts, and misuse of public resources. Government offices became the epicentres of crime, a pattern that persists to this day.

Colonial Roots of Corruption

Corruption in Kenya did not begin with independence. During the colonial era, it was the preserve of British administrators, loyalists, and the 25,000-strong home guard battalion. These groups exploited the native population through land alienation, forced labour, and extortion. The home guards, eager to please their colonial masters, became notorious for their brutality and greed. They were rewarded with land, positions, and influence—privileges that their descendants continue to enjoy. The colonial chiefs, described as corrupt, inefficient, and tyrannical, were collaborators who oppressed their own people to advance both colonial interests and personal gain.

One of the most infamous colonial-era scandals was the 1955 Mbotela and Ofafa housing project. The project was riddled with kickbacks, inflated costs, and substandard materials.

Everyone was implicated, from Asian contractors to the city mayor, Israel Somen, and the chief engineer, Harold Whipp. Whipp, under investigation for multiple acts of corruption, including tampering with his own water meter, committed suicide before he could be dismissed. This scandal set a precedent for the misuse of public funds that would later define post-independence Kenya.

Independence and the Birth of a New Elite

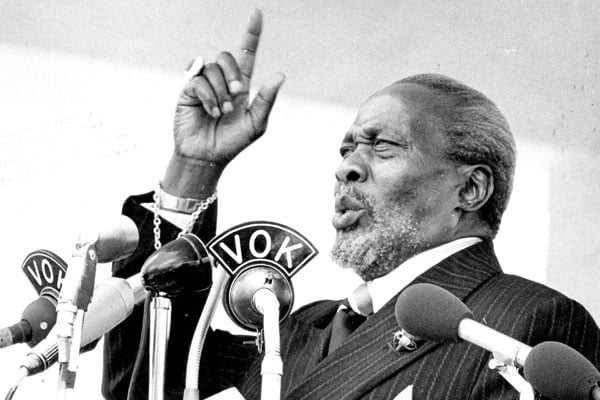

When Kenya gained independence in 1963, the expectation was that the new African leadership would dismantle the exploitative systems of the colonial regime. Instead, the new elite inherited and perfected them. One of Jomo Kenyatta’s first acts as Prime Minister was to order a Rolls Royce from London—without budgetary provision or intent to pay.

At a time when the country was financially strained, this act symbolized the emerging culture of entitlement among the political class. Ironically, Kenyatta later reprimanded Nairobi Mayor Charles Rubia for attempting to purchase a similar car, leading to Rubia’s resignation. The hypocrisy was glaring: the leadership preached austerity while practicing extravagance.

The Maize Scandal and the Normalization of Theft

Kenya’s first major post-independence corruption scandal involved maize.

In 1964–65, Paul Ngei, a member of the Kapenguria Six and Minister for Marketing and Cooperatives, was accused of smuggling and exporting surplus maize, leading to domestic shortages. The government was forced to import yellow maize from the United States to avert famine. Although Ngei resigned and his ministry was disbanded, he faced no real consequences. Years later, in 1971, he drove off with a Mercedes Benz from DT Dobie without paying, claiming he was merely following the example of the “father of the nation.” This impunity sent a clear message: corruption was not only tolerated but rewarded.

By failing to hold Ngei accountable, Kenyatta set a dangerous precedent. The political elite learned that loyalty to the presidency was more valuable than integrity. The result was a feeding frenzy among ministers, provincial commissioners, and senior civil servants. Public office became a gateway to personal enrichment.

The Gatundu Self-Help Hospital and the Politics of Patronage

Kenyatta’s favourite charity, the Gatundu Self-Help Hospital, became a symbol of how philanthropy was used to mask corruption. High-profile visitors were expected to donate generously, and countless fundraisers were held in its name. However, much of the money raised never reached the hospital. It was an open secret that the project was a “self-help” initiative in the literal sense—Kenyatta’s inner circle helped themselves to the proceeds. This culture of patronage entrenched the idea that proximity to power was the surest path to wealth.

The Rise of “Mr. Ten Percent”

The post-independence years saw unprecedented greed. Politicians and bureaucrats scrambled to acquire land, shares in foreign companies, and government contracts. Trade Minister Dr. Julius Kiano, the first Kenyan to earn a PhD, became infamous as “Mr. Ten Percent” for demanding kickbacks on deals under his ministry.

Despite widespread knowledge of his actions, Kenyatta neither reprimanded nor dismissed him. The silence from the top was interpreted as approval. Corruption had become systemic, woven into the fabric of governance.

Legacy of the Home Guards

The continuity between colonial and post-colonial corruption is striking. The children and grandchildren of the home guards—those who collaborated with the British—remain among Kenya’s wealthiest and most powerful families. They inherited not only land and privilege but also the mindset that public office is a tool for personal gain. Meanwhile, the majority of Kenyans continue to bear the burden of inequality, unemployment, and poverty.

Conclusion

Corruption in Kenya did not emerge overnight. It evolved from colonial exploitation, was legitimized by the Ndegwa Commission, and was entrenched by the political elite after independence. What began as collaboration with foreign rulers transformed into a homegrown system of plunder. Burudi Nabwera’s warning in 1974 was not merely rhetorical—it was prophetic. The cancer of corruption has metastasized through every institution, eroding trust, justice, and national progress. Until Kenya confronts this legacy with honesty and accountability, the ghosts of the past will continue to haunt its future.