Over the centuries, countless young Africans have asked how the continent—once home to some of the world’s most advanced civilizations—became the target of successive waves of conquest, enslavement, and exploitation by foreign powers.

These questions are not easily answered. They demand a deep historical and scientific understanding of how Africa’s civilizational trajectory was interrupted, dismantled, and redirected by external invasions and internal dislocations. The truth is neither simple nor comforting: Africa’s subjugation was not the result of collective failure or collaboration, but of being systematically disarmed, divided, and overwhelmed by forces that had already weaponized science, technology, and organization for imperial expansion.

The Myth of Collaboration and the Reality of Conquest

Contrary to popular narratives, most Africans did not willingly participate in their own destruction. The majority were unarmed, unprepared, and unaware of the scale of the demographic and military onslaught that would engulf them.

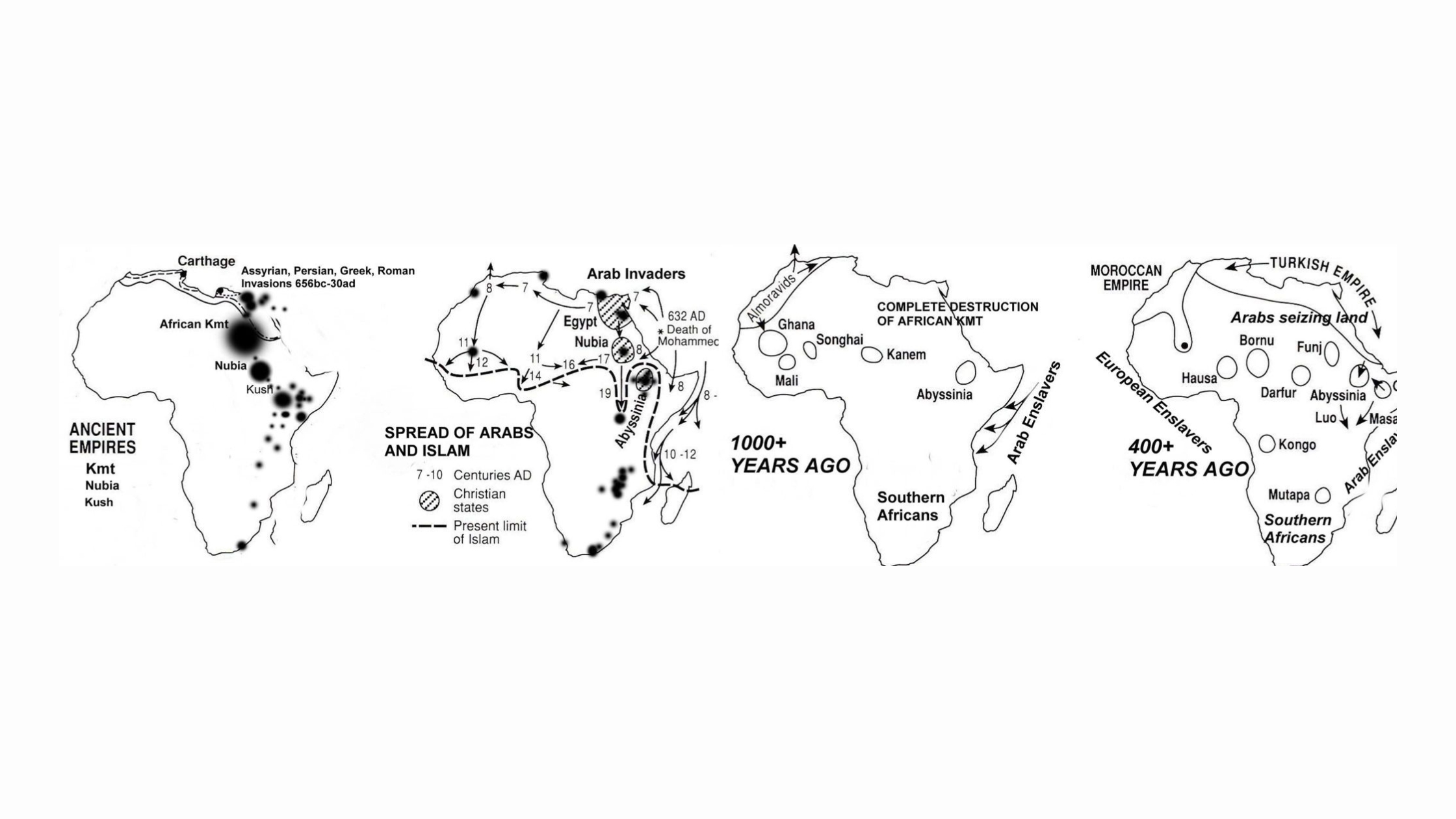

The invasions that reshaped the world from 650 BCE onward were driven by populations fleeing ecological and political crises in Eurasia and North Africa.

These groups—first Assyrians, then Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and later Europeans—expanded outward in search of new lands and resources. In the process, they seized over three-quarters of the world’s habitable landmass, displacing indigenous populations and erasing entire civilizations. Africa, rich in resources but weakened by earlier invasions, became a prime target.

The Fall of the Nile Valley Civilizations

The destruction of Africa’s Nile Valley civilizations of Kmt (Egypt), Nubia, Kush, and Kerma marked a turning point in world history. These societies were not primitive kingdoms but highly organized, literate, and scientifically advanced states.

They developed centralized bureaucracies, planned economies, irrigation systems, and standing armies. Their engineers built monumental architecture and managed complex agricultural systems that sustained millions. Their scholars pioneered mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and philosophy. These civilizations represented Africa’s civilizational shield—its capacity to organize, defend, and innovate on a continental scale.

The collapse of this shield was not a natural decline but a series of deliberate destructions. Assyrian invasions in the seventh century BCE devastated Thebes and crippled Kmt’s political core. Persian conquest followed, imposing tribute and dismantling indigenous governance.

Greek rule under the Ptolemies redirected the Nile’s wealth toward Mediterranean interests, appropriating African knowledge while excluding Africans from power.

Roman occupation intensified extraction and militarization, turning Kmt into a grain colony for the empire.

By the time Arab-Islamic armies arrived in the seventh century CE, the region’s institutions had been hollowed out. Arab rule completed the process, absorbing African intellectual traditions into new imperial frameworks while erasing their origins.

Civilizational Decapitation and Its Aftermath

The cumulative effect of these invasions was civilizational decapitation. Africa lost its most advanced centers of literacy, engineering, and statecraft. Knowledge that had once circulated within African academies and temples was extracted, translated, and rebranded as foreign discovery.

The continent’s political fragmentation deepened as centralized states gave way to smaller, isolated polities. Trade networks that once linked the Nile to the Niger and beyond were severed. Without the institutional capacity to coordinate large-scale defense or technological innovation, Africa became vulnerable to the next waves of conquest—the trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, and Atlantic slave trades.

Over a span of 1,400 years, these systems of enslavement and extraction destroyed the lives of hundreds of millions of Africans. They drained the continent of its human capital, disrupted its demographic balance, and entrenched dependency on external powers.

Yet even amid devastation, African societies adapted, resisted, and rebuilt. The resilience of African cultures, languages, and spiritual systems remains one of history’s most remarkable testaments to human endurance.

The Present Crossroads

Today, the historical cycle that began over two millennia ago is nearing its organic end. The global order that once thrived on African subjugation is fracturing under its own contradictions.

For the first time in centuries, African youth stand at a pivotal moment in history. With access to knowledge, technology, and global networks, they possess the potential to reverse the long arc of dispossession. But potential alone is not enough. Without mastery of science, engineering, and organizational systems, Africa risks repeating the vulnerabilities of the past.

The lesson of history is clear: civilizations fall not merely because they are conquered, but because they fail to adapt to the changing technological and organizational realities of their time.

The next two generations of Africans must therefore become the architects of a new civilizational renaissance—one grounded in scientific literacy, economic self-determination, and cultural confidence. The reclamation of Africa’s future depends not on nostalgia for past glory, but on the disciplined reconstruction of its intellectual and institutional foundations.

Toward a New African Epoch

The story of Africa’s subjugation is not a tale of eternal victimhood but of interrupted greatness. The same continent that gave birth to the world’s earliest sciences, philosophies, and state systems can once again lead in innovation and human development. But this requires a collective awakening—a recognition that the struggle for liberation is no longer fought with swords or slogans, but with laboratories, data, and disciplined organization.

History has shown what happens when Africa’s civilizational shield is broken.

The task now is to rebuild it, not as a fortress of isolation, but as a foundation for global contribution and self-determined progress. The next chapter of African history will be written not by those who lament the past, but by those who understand it deeply enough to transform the future.